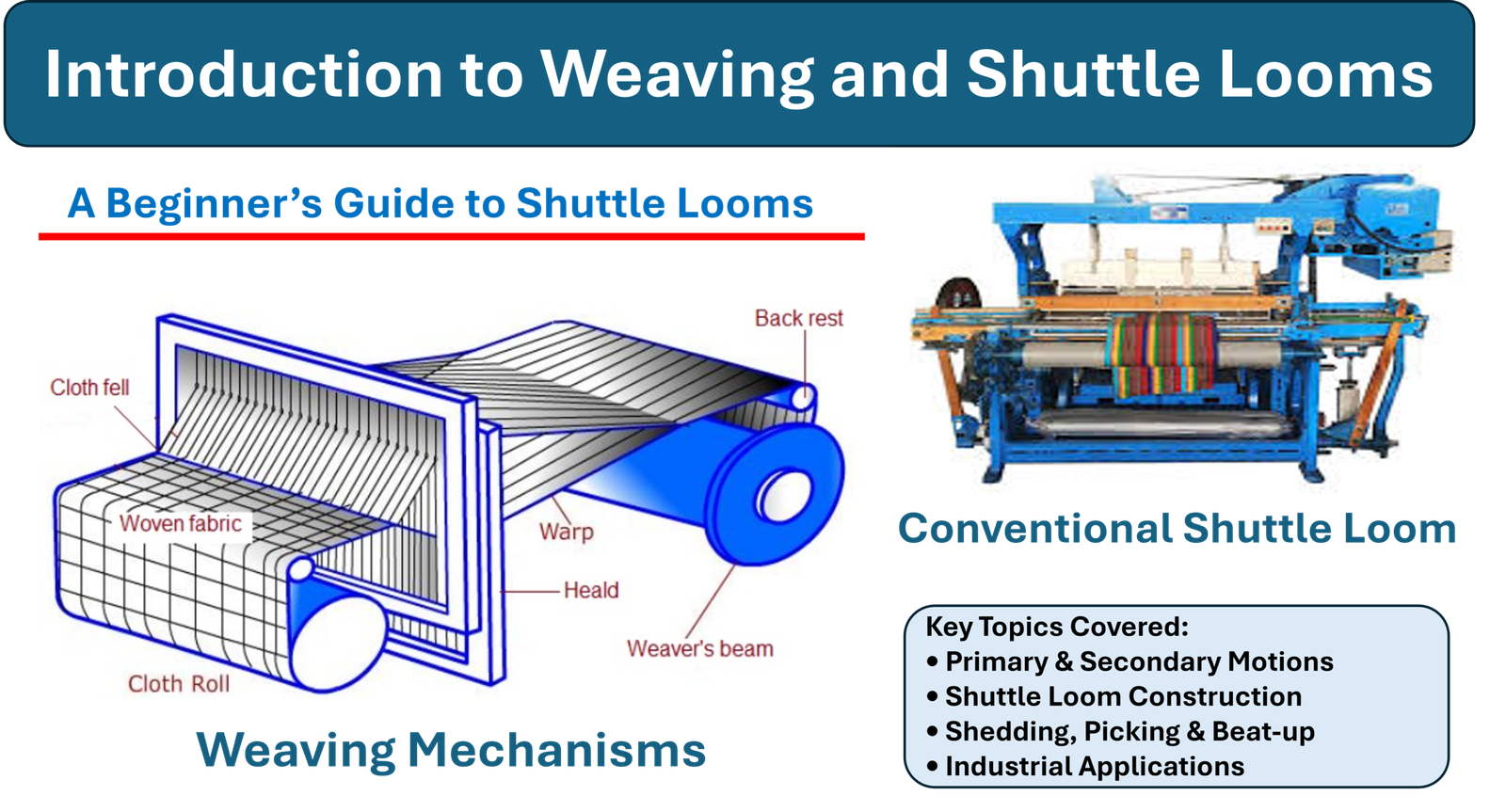

1. Introduction

Weaving is one of the oldest and most fundamental methods of fabric formation in textile engineering. At its core, weaving involves the systematic interlacing of two distinct sets of yarns, warp (lengthwise) and weft (crosswise), to produce a stable and durable fabric structure. Although weaving techniques date back thousands of years to early civilisations such as those of Ancient Egypt and Ancient India, the fundamental principle of interlacing perpendicular yarn systems remains unchanged even in today’s highly automated textile mills.

In fabric manufacturing, weaving stands alongside knitting, nonwovens, and braiding as a principal method of producing flexible, two-dimensional textile structures. Its importance lies in its ability to engineer fabric properties such as strength, coverage, drape, air permeability, and durability simply by varying yarn characteristics and interlacing patterns. For undergraduate textile engineers, a clear understanding of weaving technology is essential because most conventional apparel fabrics and many industrial textiles are woven. Moreover, loom mechanics directly influence productivity, production cost, and fabric quality, making weaving knowledge foundational for fabric design, production planning, and quality control.

Among the various types of weaving machines, the shuttle loom represents the classical form of power-driven weaving. Historically, the invention of the flying shuttle marked a turning point in textile manufacturing by significantly increasing weft insertion speed and enabling mechanised production. In shuttle looms, the weft yarn wound onto a pirn is carried across the warp by a wooden shuttle that moves back and forth between the loom sides. This mechanism transformed hand weaving into an industrial-scale operation and laid the foundation for the mechanisation of the textile industry during the Industrial Revolution.

Although modern textile mills increasingly rely on shuttleless looms for higher speeds, lower noise levels, and improved efficiency, shuttle looms remain highly significant in education and small-scale production sectors. Their simple construction clearly demonstrates the primary weaving motions, shedding, picking, and beating-up, making them ideal for teaching the mechanical principles of weaving. Additionally, in decentralised power-loom sectors and for certain traditional or narrow fabrics, shuttle looms continue to offer advantages such as flexibility, lower capital investment, and ease of maintenance.

This beginner’s guide aims to build a strong conceptual foundation in weaving technology, with a particular focus on shuttle looms. By understanding how warp and weft interact within the loom mechanism, students can confidently progress to advanced topics such as loom automation, fabric engineering, and technical textile development.

2. Basic principles of weaving motions

In a conventional loom, fabric formation is achieved by a sequence of coordinated motions acting on warp and weft. For beginners, it helps to relate each motion to a simple real-life activity:

2.1 Warp and weft

Warp: The set of longitudinal yarns held under tension and wound from a warp beam to a cloth beam; each individual warp yarn is called an end.

Weft: The transverse yarns inserted across the width; each individual weft yarn is called a pick.

2.2 Shedding

Definition: The process of dividing the warp sheet into two layers (top and bottom) to form a tunnel (shed) for the weft or weft carrier to pass through.

Mechanism: Groups of warp ends are lifted or lowered by heald frames (harnesses) controlled by cams, dobby, or Jacquard mechanisms.

2.3 Picking

Definition: The action of inserting the weft or weft-carrying device (shuttle in a shuttle loom) through the open shed.

On shuttle looms, a picking mechanism accelerates the shuttle from one box, sends it through the shed, and receives it in the opposite box.

2.4 Beating-up (beat-up)

Definition: The action of pushing the newly inserted pick-up to the cloth fell (the line where the fabric is fully formed) using the reed carried by the sley.

The sley oscillates, and the reed, acting like a comb, packs each pick into its final position.

2.5 Take-up motion

Definition: The mechanism that continuously or intermittently winds the newly formed fabric onto the cloth beam after beat-up.

It controls picks per centimetre (or inch) by adjusting the rate at which cloth is withdrawn from the fell.

2.6 Let-off motion

Definition: The mechanism that releases fresh warp from the warp beam at a controlled rate to maintain approximately constant warp tension as the cloth is taken up.

Take-up and let-off work together; if the cloth is pulled faster, more warp must be released to avoid excessive tension.

Together, shedding, picking, and beat-up are called the primary motions of weaving, while take-up and let-off are secondary motions that ensure continuous fabric production at uniform construction. Auxiliary motions, such as warp stop motion, weft stop motion, and warp protector motion, are added to stop the loom in case of end or pick breakage or shuttle trapping, protecting both fabric and machine.

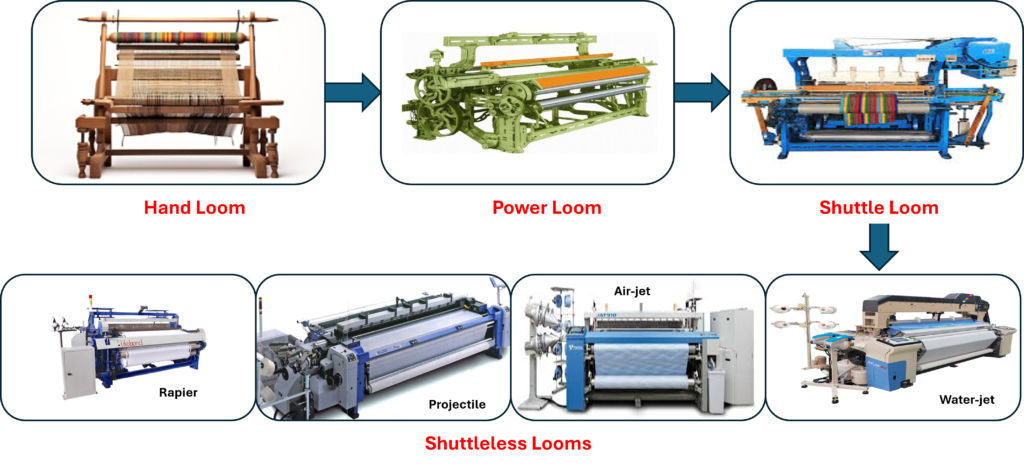

3. Types of Looms

Looms can broadly be classified into:

- Hand Looms – Manually operated; low production; used in traditional weaving.

- Power Looms – Mechanically driven; higher speed than handlooms.

- Shuttle Looms – Use a shuttle to carry weft yarn.

- Shuttleless Looms – Use alternative weft insertion methods such as:

- Rapier

- Projectile

- Air-jet

- Water-jet

Among these, the shuttle loom is historically and academically significant.

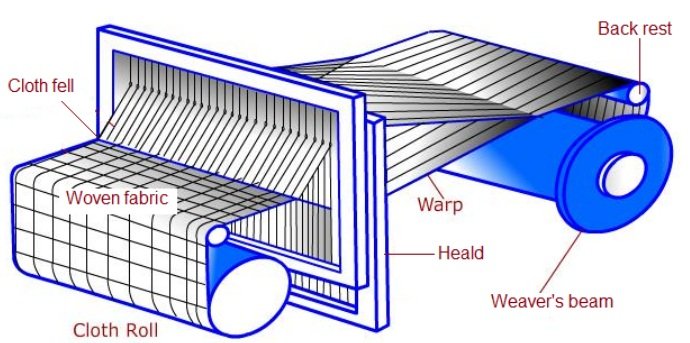

4. Shuttle loom: construction, parts, motions, and working

4.1 Construction and main parts

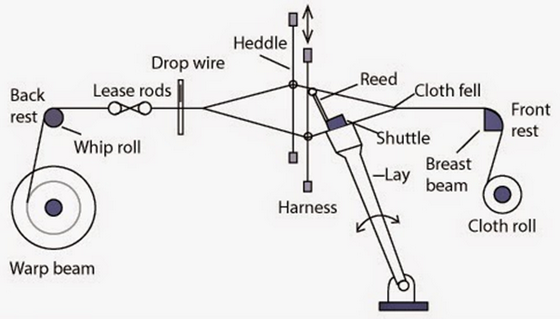

A traditional shuttle loom consists of a rigid frame that supports the warp path, shedding devices, picking mechanism, and cloth winding system. Key parts and their functions include:

- Loom frame and side frames: The main structural members that carry shafts, bearings, and mechanisms.

- Warp beam (weaver’s beam): A flanged beam at the back that carries thousands of parallel warp ends wound at controlled tension.

- Back rest (whip roll): A roller over which the warp passes to help control the warp sheet path and tension.

- Heald frames (harnesses) with healds: Rectangular frames containing many heald wires (or heddles), each with an eye through which warp ends pass; they move up and down to form sheds according to the weave pattern.

- Reed and sley (lay): The reed is a metallic comb clamped in the sley; the sley oscillates to bring the reed forward for beat-up and backwards to allow shuttle passage.

- Shuttle and shuttle boxes: The shuttle is a boat-shaped wooden carrier containing a pirn of weft yarn; shuttle boxes are at each end of the sley house and control the shuttle at the end of each pick.

- Picking mechanism: Includes picking cam (or tappet), picking bowl, picking stick, pickers, and associated linkages used to accelerate the shuttle from one box into the shed.

- Checking mechanism: Slows and arrests the shuttle as it enters the opposite box to prevent damage.

- Take-up mechanism: Positively or negatively driven mechanism to rotate the cloth roller and control pick density.

- Let-off mechanism: Frictional or positive system that rotates the warp beam to release warp under controlled tension.

- Stop motions (auxiliary): Warp stop motion with drop wires, weft stop motion, and warp protector motion to stop the loom in case of yarn breakage or shuttle trapping.

4.2 Motions of the shuttle loom

- Primary motions

- Shedding: Movement of heald frames to create the shed.

- Picking: Insertion of the shuttle carrying weft through the shed.

- Beat-up: Movement of sley and reed to compact the pick at the cloth fell.

- Secondary motions

- Take-up: Winding woven cloth on the cloth beam at a set rate.

- Let-off: Releasing warp from the warp beam to maintain tension.

- Auxiliary motions

- Warp stop motion (drop wires and feelers) to stop the loom on warp break.

- Weft stop motion to stop on weft break or weft exhaustion.

- Warp protector or shuttle protector motion to stop the loom if a shuttle is trapped in the shed and prevent reed or warp damage.

4.3 Working sequence (one weaving cycle)

In each loom revolution, the following sequence is coordinated by cams, gears, and crank mechanisms:

- Shedding

- Selected heald frames rise, and others fall to form the required shed according to the weave repeat at a defined crank angle.

- Picking

- Once the shed is sufficiently open, the picking cam drives the picking stick, which transfers energy to the picker and propels the shuttle from one box into and across the shed.

- The shuttle drags weft from the pirn, leaving a pick of yarn across the warp sheet.

- Checking and preparation for the next pick

- The checking mechanism decelerates and stops the shuttle in the opposite box; shuttle position is monitored by shuttle feelers to ensure correct boxing.

- Beat-up

- As the sley moves forward, the reed pushes the newly inserted pick into the cloth fell, setting the pick spacing.

- The sley then swings back, creating space for the next shuttle passage.

- Take-up and let-off

- The take-up mechanism advances the cloth roller to wind a small length of fabric.

- The let-off releases an equivalent length of warp so that warp tension remains approximately constant.

This cycle repeats for every pick, with shedding patterns, shuttle direction, and loom motions synchronised to build the desired fabric structure from warp and weft.

5. Advantages of shuttle looms

For a teaching and small-mill context, shuttle looms offer several advantages:

- Fabric versatility: Capable of producing a wide range of simple and complex weaves (plain, twills, satins, checks, stripes) using cam, dobby, or Jacquard shedding systems.

- Firm selvedge: Produce well-bound selvedge because the weft is continuous from edge to edge, with the shuttle turning at each side.

- Low capital cost: Lower initial investment compared to modern high-speed shuttleless looms, making them attractive for small power-loom sectors.

- Simplicity and robustness: Mechanically rugged, relatively easy to maintain with basic skills and tools.

- Educational value: Very suitable for demonstrating fundamental weaving motions (shedding, picking, beat-up, take-up, let-off) to students.

6. Disadvantages and limitations

However, shuttle looms also have important limitations relative to modern shuttleless looms:

- Lower speed: Weft insertion rate is limited by the heavy shuttle’s acceleration and deceleration; high speeds increase noise, vibration, and yarn damage.

- High noise and vibration: Repeated shuttle impacts and beat-up cause high sound levels and structural vibration, contributing to fatigue and less comfortable working conditions.

- More mechanical wear and maintenance: Picking mechanisms, shuttle boxes, and checkers are subject to heavy mechanical loads, requiring frequent maintenance and adjustment.

- Yarn damage and end breakage: Abrasion between warp and shuttle, especially at the selvages, can increase warp breakage, particularly for delicate yarns.

- Limited suitability for very wide or very high-speed fabrics: Shuttle interference with warp and the mass of the shuttle restrict economically feasible width and speed.

7. Industrial applications

Even with the expansion of shuttleless technology, shuttle looms still find use in specific sectors:

- Small-scale apparel and furnishing fabric production in decentralised power-loom clusters, where low capital cost is critical.

- Traditional fabrics (e.g., certain checks, stripes, and regional handloom-inspired designs) where construction and aesthetics have been historically developed on shuttle looms.

- Narrow-width fabrics and tapes are used when simple shuttle looms, or narrow looms, are used in cottage and small workshop environments.

- Educational laboratories in textile institutes for teaching basic weaving mechanisms and conducting introductory experiments on loom timing and motions.

8. Shuttle vs shuttleless loom: simple comparison

| Feature | Shuttle Loom | Shuttleless Loom |

| Speed | Moderate weft insertion rate, limited by heavy shuttle acceleration and checking. | High weft insertion rate using light carriers (projectile, rapier, airjet, waterjet). |

| Efficiency | More stoppages due to shuttle wear, yarn abrasion, and pirn changes; lower overall efficiency in mass production. | Fewer mechanical impacts, automatic weft supply, and improved stop motions increase weaving efficiency in modern mills. |

| Maintenance | Frequent maintenance of picking, shuttle boxes, and checking; many moving parts are subject to wear. | Different maintenance focus (no shuttles); fewer heavy-impact parts, but more precision components (nozzles, grippers, electronics). |

| Noise | High noise due to shuttle impacts and beat-up shocks; noisy weave room environment. | Generally, lower noise levels, especially in airjet and rapier looms, improve working conditions. |

| Fabric quality | Good, firm selvedge; possible warp abrasion and occasional shuttle-related defects (flying shuttle, broken selvedge). | Better surface quality and fewer shuttle marks; broader product range, but selvedge control is by special devices rather than continuous weft. |

9. Conclusion and learning outcomes

Shuttle loom technology provides the classical foundation of weaving, demonstrating how warp and weft interlace through coordinated primary, secondary, and auxiliary motions. Even though modern weaving has moved towards faster, quieter shuttleless systems, understanding shuttle loom construction and operation remains essential for textile students because many fabric faults, design decisions, and process optimisations are still interpreted using this basic model.

References

- Booth, J. E. (2004). Textile mathematics: Volume 3 – Spinning, weaving, knitting and weaving calculations (3rd ed.). The Textile Institute.

- Lord, P. R., & Mohamed, M. H. (1992). Weaving: Conversion of yarn to fabric. Merrow Publishing.

- Talukdar, M. K., Sriramulu, P. K., & Ajgaonkar, D. B. (1998). Weaving: Machines, mechanisms, management. Mahajan Publishers.

- Ormerod, A., & Sondhelm, W. S. (1995). Weaving: Technology and operations. Textile Institute.

- Adanur, S. (2001). Handbook of weaving. CRC Press.

- Mark, R., & Robinson, G. (Eds.). (1986). Principles of weaving. The Textile Institute..

- Textile Learner. (2024, December 12). Basic Weaving Techniques for Beginners.

https://textilelearner.net/weaving-preparatory-process/ - Textile Sphere. (2021, November 6). Warping process in weaving: Importance, types, assessment.

https://www.textilesphere.com/2021/11/warping-process-in-weaving.html

About the author: Dedicated PhD scholar at NIT Jalandhar with a recent Master's from NIFT New Delhi. Over a decade of expertise in the textile industry, spanning home furnishings, velvet, carpet, bedsheets, suiting, and shirting. Successful in roles like Shift In-Charge, Manufacturing Manager, and Training Manager. Successfully empowered Omani women in textiles through the Oman government (NTF) sponsored training program. Driven by a passion for the industry, committed to advancing sectoral excellence. Proficient in analytical thinking, innovation, and continuous improvement. Eager to acquire new knowledge, tackle challenges, and collaborate effectively in diverse teams. A valuable asset to organisations sharing the same vision and values.

Read More

- Handloom to High Street: Why Traditional Textiles Matter Today

- Lean Manufacturing Tools in the Textile & Apparel Industry

- CO₂ vs Water Dyeing: A Sustainable Comparison

- The Rise of Sustainable Textile Insulation Materials

- Innovations in Smart Textiles for Wearable Comfort

- Recent Advancements in Weaving Technology

- Wyzenbeek vs Martindale: Fabric Test Comparison

- Differences Between SAM and SMV in Garment Manufacturing

- Exploring the Future: Smart Textiles and Their Influence on Technological Innovation

- China’s Cotton Topping Robot: Revolutionizing Xinjiang’s Fields at 10x Speed

- Smart Garments for Elderly Health Monitoring and Active Living

- Call for Submissions: Share Your Expertise in Textile and Apparel

- Redesigning the Breath of Life: A Next-Gen N95 That Filters More Than Air

- History and Development of Suture