Introduction:

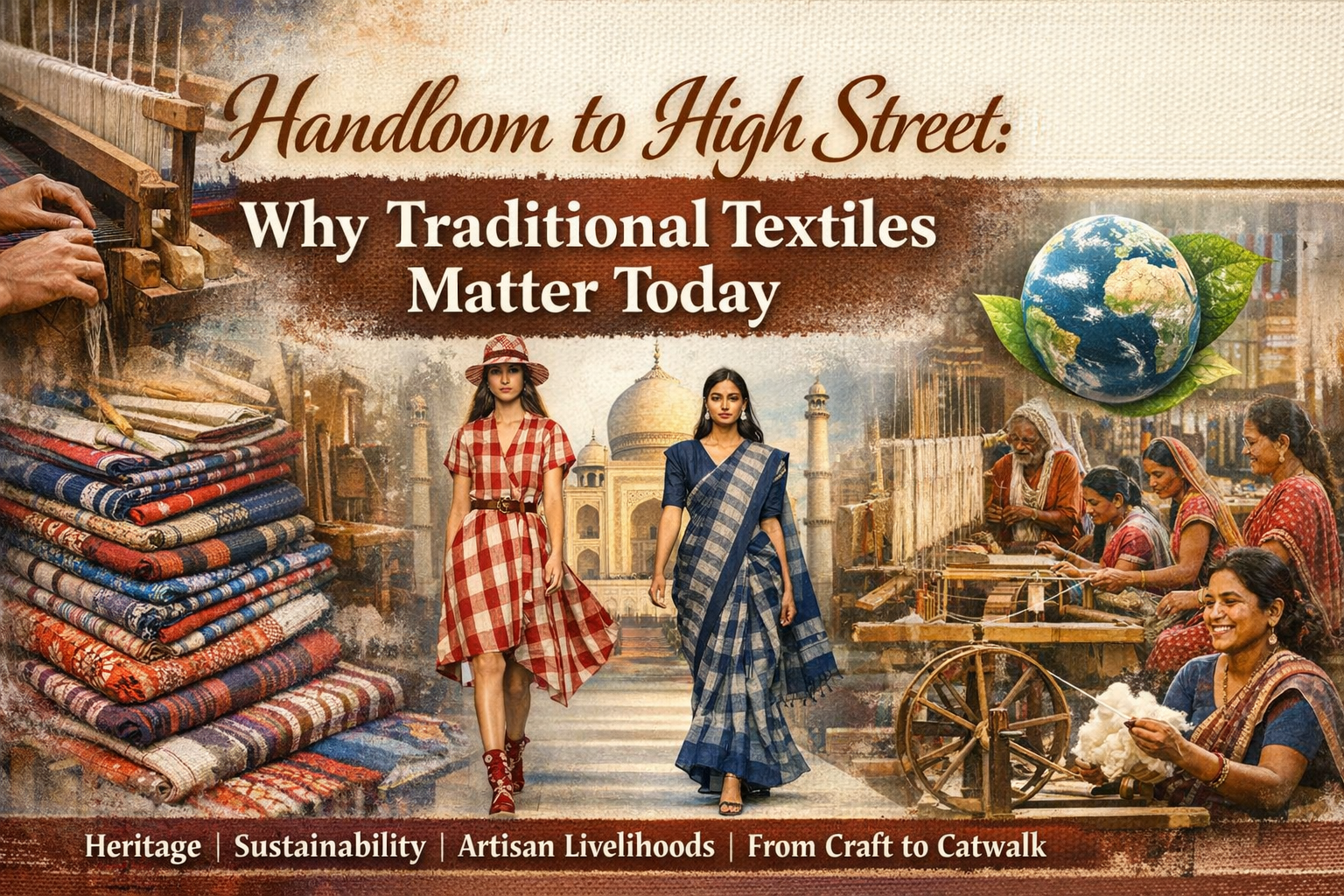

Traditional and handloom textiles encompass a wide range of woven, dyed, and embellished fabrics produced on non-mechanized looms using regionally embedded skills and knowledge systems. These textiles historically served everyday, ceremonial, and status functions in local communities but are increasingly visible in contemporary silhouettes, designer collaborations, and even global trend forecasts.

- Recent research on traditional handcrafting and slow fashion shows that heritage techniques are being integrated into alternative business models that prioritise locality, transparency, and social equity, challenging the speed‑ and volume-driven logic of fast fashion.

- Case studies on Bangladeshi Gamcha, Indian handloom clusters, and indigenous fibre initiatives illustrate how “from craft to catwalk” narratives can simultaneously promote cultural preservation, design innovation, and new markets.

For students and professionals, this evolving landscape demands fluency in both technical processes and the socio-cultural stories that make these textiles valuable in modern apparel.

Historical and Cultural Significance:

Traditional textiles encode histories of trade, technology, and identity stretching back millennia. Indian sources alone document cotton spinning from 4000 BCE and the production of dyed fabrics in the Indus Valley, with the handloom evolving into a central symbol of anti-colonial resistance during the Swadeshi and Khadi movements.

- The coffee‑table volume Sustainability in the Handloom Traditions of India shows how each regional weave (Banaras brocade, Kanjeevaram, Jamdani, Muga, Balaramapuram, Ashavali, etc.) carries distinct motifs, rituals, and social meanings, often tied to specific communities, climates, and local ecologies.

- Essays on Naga, Assamese, and other North‑East traditions emphasise cloth as identity—where tribal or community affiliation is literally worn on the body, and motifs function as visual archives of myths, status, and territory.

A complementary literature review on handloom sustainability underlines that these cultural dimensions are a key reason handloom retains demand despite economic pressures; textiles are read as heritage objects rather than mere commodities.

From Craft to Commerce:

Recent work documents how handloom has travelled from local craft economies into national and global fashion markets through recontextualization and creative design.

- The 2025 paper “From Craft to Catwalk: Handloom Stories in Modern Silhouettes” analyses how Gamcha, once a low-status utilitarian cloth associated with rural labour, is being used in dresses, jumpsuits, fusion wear, and couture-style gowns for urban and international consumers.

- Designers like Bibi Russell and emerging Bangladeshi brands rework Gamcha checks into contemporary silhouettes, demonstrating how traditional fabrics can support streetwear, resort wear, and occasion wear while maintaining recognisable pattern vocabularies.

- In India, case narratives on brands and collectives such as Rangsutra, Kala Cotton (Khamir), Looms of Ladakh, and others show how handloom products are being positioned within fair‑trade, lifestyle, and export markets rather than only ceremonial or local use.

Policy and export data from National Handloom Day 2025 confirm that India now supplies about 95% of the world’s hand-woven fabric, exporting made-ups, floor coverings, and apparel to over 20 countries, with strong demand from the United States, UAE, and Europe.

Sustainability and Slow Fashion:

The uploaded review article on traditional handcrafting and sustainability frames handloom and other heritage crafts squarely within the slow fashion paradigm.

- Traditional techniques (hand weaving, hand‑spinning, natural dyeing, repair) use minimal fossil fuel energy, generate little waste, and rely heavily on local renewable materials—making their ecological footprint far lower than industrial fast fashion.

- The Indian handloom volume documents extensive use of natural dyes, indigenous fibres (hemp, jute, bamboo, kala cotton, Eri silk, Muga), water-saving practices, upcycling (khesh, chindi durries), and zero-waste habits embedded in rural life.

- Essays on Rangsutra, AIACA’s Craftmark Green certification, and green pilot projects show how handloom enterprises are integrating effluent‑treatment plants, BCI cotton, rainwater harvesting, and Azo-free dyes to meet contemporary sustainability standards while retaining handicraft.

At the same time, both the sustainability review and handloom-specific studies highlight tensions: labour-intensive techniques, long production times, and small-scale operations raise unit costs, making slow, hand‑made products structurally misaligned with fast‑fashion pricing and speed.

Socioeconomic Impact and Artisan Livelihoods:

The review “Sustainability of Handloom: A Review” and the handloom livelihoods essays converge on handloom as one of rural India’s largest non-farm employment generators.

- The 4th All India Handloom Census and Ministry of Textiles data, cited in these documents, indicate over 31–35 lakh handloom worker households in India, with a large majority belonging to socially and economically marginalised groups and around 70–72% of economic weavers being women.

- Studies summarised in the review identify chronic issues: low wages, lack of working capital, exposure to health hazards, fluctuating yarn prices, and competition from power looms, alongside limited awareness of government schemes and poor access to credit and design support.

- At the same time, qualitative essays show that collective models (co-operatives, producer companies, social enterprises like Rangsutra, KHAMIR, 7Weaves, Looms of Ladakh) can significantly enhance incomes, leadership, and self-esteem while anchoring livelihood in local fibres and ecosystems.

Government documents on National Handloom Day describe extensive policy support—including NHDP, Raw Material Supply Scheme, MUDRA loans, Handloom Mark and India Handloom Brand, cluster development, marketing assistance, GI registrations, e-commerce integration, and producer companies that together aim to stabilise incomes and create direct weaver–market linkages.

Innovation and Adaptation:

Far from being static, the uploaded materials show that traditional textiles are sites of intense innovation—from design and technology to pedagogy and business models.

- The Gamcha study systematically documents how a basic checked towel is transformed into gowns, jumpsuits, halter‑neck dresses, and fusion garments aligned with Spring/Summer 2026 global trends (colour palettes, silhouettes, fabric directions), demonstrating precise alignment of heritage textiles with future-oriented fashion forecasting.

- The sustainability review describes technology-led innovations (e.g., digital design tools, biomaterials, circular systems) and emerging digital methods for craft (such as GAN-based motif generation in related Jamdani research cited within the Gamcha paper), suggesting pathways for integrating AI and CAD into handloom design while respecting heritage forms.

- Indian handloom essays highlight innovations in fibre (Kala cotton, indigenous wools, Eri, forest-linked fibres), solar-powered looms, cluster-level design interventions, and experiments with contemporary silhouettes and lifestyle products while preserving core techniques.

- Education-focused pieces (e.g., Judy Frater’s work in Kutch) demonstrate how design education for artisans leads to recognisable personal styles, higher incomes, awards, and the return of younger generations to craft as a desirable profession.

Challenges Facing Traditional Textiles:

Despite their strengths, the PDFs collectively underline several structural challenges that must be confronted if handloom and traditional textiles are to remain viable in mainstream fashion.

- Economic and operational pressures: Slow, labour-intensive production raises costs and limits scalability; attempts to industrialise traditional techniques risk eroding authenticity and craft identity.

- Competition from mass production: Cheap power‑looms and synthetic fabrics undercut prices. At the same time, lack of design support and weak branding make it hard for traditional products to compete in fashion-driven markets.

- Skill loss and generational shifts: Several essays (e.g., on Muga silk, Bavanbutti, and other endangered weaves) document dwindling numbers of master weavers and youth moving to different jobs, often due to low and unstable incomes and climate or pollution stresses on raw‑material systems.

- Market access and knowledge gaps: The handloom review shows low awareness of key government schemes (often under 15% of weaver households for many programmes), plus limited marketing and digital capabilities, constraining the potential benefits of policy support.

- Cultural appropriation and inequity: The sustainability review warns that uncredited commercial use of motifs, or surface-level adoption of traditional techniques without community participation and fair compensation, constitutes cultural appropriation and undermines both heritage and livelihoods.

Future Relevance: Why Traditional Textiles Matter for Fashion Education and Industry:

Drawing together all the uploaded research, traditional and handloom textiles emerge as central—not peripheral—to the future of sustainable fashion and apparel education.

- Integrated sustainability model: Handloom inherently combines environmental, social, cultural, and economic sustainability: low‑energy, often bio-based production; decentralised rural employment; deep cultural content; and potential for premium, narrative-rich products.

- Alternative economic imaginaries: The “we‑economy” and slow fashion frameworks propose collaborative, community-centred business models where value is tied to craftsmanship, locality, and longevity rather than volume and speed.

- Pedagogical laboratory: For fashion and textile schools, handloom provides concrete material to teach lifecycle thinking, participatory design, rural–urban collaborations, and the politics of fashion, supported by real data on exports, employment, and policy initiatives.

- Market opportunity aligned with values: The Gamcha study and export statistics indicate a growing consumer appetite for sustainable, story-driven products, and predict that by 2026, a substantial share of customers will actively prefer such apparel, aligning traditional textiles with future market demand.

Embedding traditional and handloom textiles into mainstream fashion education and industry practice, therefore, means treating them as contemporary design partners and strategic sustainability assets, not as relics of the past. The uploaded research shows that when heritage, innovation, and equity are combined, “handloom to high street” is not just a slogan but a viable pathway for transforming how fashion is designed, produced, taught, and valued today.

References:

- Taj, M. M., & Fairooz, D. (2025). From craft to catwalk: Handloom stories in modern silhouettes—A study on creative applications by Gamcha for preserving Bangladesh’s cultural heritage. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Analysis, 8(10), 5468–5477. https://doi.org/10.47191/ijmra/v8-i10-02

- Vishali, & Singh, B. (2024). The resurgence of traditional textiles in 21st century fashion design. International Journal of Home Science, 10(3), 32–36.

- Mishra, S. S., & Mohapatra, A. K. D. (2020). Sustainability of handloom: A review. Ilkogretim Online – Elementary Education Online, 19(3), 1923–1940. https://doi:10.17051/ilkonline.2020.03.735348

- Rajput, E. B., & Kurien, D. (2025). Trends in handloom marketing research. International Journal of Creative Research Thoughts, 13(9), a525–a532.

- Chowdhury, N. (2025). Cultural sustainability in fashion: Weaving heritage into modern design. Journal of Emerging Technologies and Innovative Research, 12(7), a921–a924.

- Koutsou, V., Zoumaki, M., Lykourioti, I., & Korlos, A. (2025). The role of traditional handcrafting in promoting sustainability: A literature review. Design+, 2(3), 025190027. https://doi.org/10.36922/DP025190027

- Press Information Bureau. (2025, August 6). National Handloom Day 2025: Weaving innovation into tradition. Government of India. https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2141924

- Centre for Environment Education. (2024). Sustainability in the handloom traditions of India. Development Commissioner (Handlooms), Ministry of Textiles, Government of India. ISBN: 978-93-84233-99-0

About the author: Dedicated PhD scholar at NIT Jalandhar with a recent Master's from NIFT New Delhi. Over a decade of expertise in the textile industry, spanning home furnishings, velvet, carpet, bedsheets, suiting, and shirting. Successful in roles like Shift In-Charge, Manufacturing Manager, and Training Manager. Successfully empowered Omani women in textiles through the Oman government (NTF) sponsored training program. Driven by a passion for the industry, committed to advancing sectoral excellence. Proficient in analytical thinking, innovation, and continuous improvement. Eager to acquire new knowledge, tackle challenges, and collaborate effectively in diverse teams. A valuable asset to organisations sharing the same vision and values.

Read More

- Lean Manufacturing Tools in the Textile & Apparel Industry

- CO₂ vs Water Dyeing: A Sustainable Comparison

- The Rise of Sustainable Textile Insulation Materials

- Innovations in Smart Textiles for Wearable Comfort

- Recent Advancements in Weaving Technology

- Wyzenbeek vs Martindale: Fabric Test Comparison

- Differences Between SAM and SMV in Garment Manufacturing

- Exploring the Future: Smart Textiles and Their Influence on Technological Innovation

- China’s Cotton Topping Robot: Revolutionizing Xinjiang’s Fields at 10x Speed

- Smart Garments for Elderly Health Monitoring and Active Living

- Call for Submissions: Share Your Expertise in Textile and Apparel

- Redesigning the Breath of Life: A Next-Gen N95 That Filters More Than Air

- History and Development of Suture